Or, Even Teachers Get The Blues

[Editor’s note: Oren Karp is a recent graduate of Brown University and a Fulbright Scholar teaching English in Kathmandu, Nepal. He posts an account of his life in Nepal every few weeks. This essay is an excerpt from his most recent posting; you can read the full essay by clicking on the link at the end of the excerpt.]

I’m writing you right now from underneath my brother Aarash (6), who is pretending to be a dog (of varying breeds) and is very disappointed that I won’t play along with him. He’s now discovered his own name in my writing and is attempting to read the rest, while positioning his entire body on top of my arm so that I can barely reach the keyboard. What he doesn’t realize is that, as the writer, I have all of the narrative leverage, and I can portray his actions however I choose. He’s attempting to ask me what I’m writing, but I’m ignoring him successfully (or so the writer would have you believe). Having realized that I’m not going to play, he’s now decided to play on his own and make both as big of a mess as he can and as much noise as possible. But I persevere.

. . .

My time at school is slowly drawing to a close as I enter my last month here, since our second term exams start next week and are followed by two weeks of vacation. After so long teaching here, the system has beaten me down and reduced me to a pure pragmatist: forget teaching my students any practical English, let’s at least see if I can prepare them for their exams, as terrible as they might be. But even when I put aside the non-linear textbook curriculum and the obscenely difficult reading passages, it’s still a massive challenge. These days, most of my classes are so far behind that I shamelessly feed students answers to questions from the textbook, just hoping to cover the material in time. But some students are absent so often that as hard as I try not to leave anyone behind, kids fall through the cracks.

There is always something new here about the educational system to make me feel frustrated, but this time what’s bothering me is a little bigger-picture. Because of a conglomeration of other factors that I’ve written about previously, students here aren’t taught to think for themselves in any real way, to try to actually understand things. It’s not that they want to take the easy way out—I’m convinced that they just don’t know any other way. When answering textbook questions about a reading, I have never seen a student compose their own original answer: instead, they look through the text for the sentence which most closely resembles an answer, and then copy that sentence directly. When they ask me to help, what they’re really asking is for me to point to the passage and show them which sentence to copy down in their notebook. As they get older, they get better at copying only the correct bits of the sentences, but not one of my students finds their own answers; not one of them reads the text, thinks about it, and writes an answer to the question from their own mind.

But I see another problem at my school, one maybe even bigger than the lack of independent thinking: the teachers seem at times to have very little respect for the students, and that really concerns me. When one of my co-teachers and I split up to give speaking tests to grade four and then met back up to share grades, I saw that where I had written students’ names by their grades, she had written their attendance roll numbers. While I say hello and hug my students arriving at school every morning, I’ve seen students greet teachers and have their namaste completely ignored. In the staff room the other day, a teacher was asking the last name of a student in grade two, and when I said that it must be the same as her older sister’s last name in grade five, all the teachers were astounded that I knew not only her last name but the fact that they were sisters, and they joked that I should be the principal.

I’m not saying that I’d do a bad job as our principal—I’d certainly have a better attendance record, at least—but I’m not sure that was my main takeaway from the interaction. I’ve seen teachers send students to go get stuff they’ve forgotten, whether it’s the whiteboard eraser or a spoon for their lunch, and, on one occasion, I even saw a teacher give a kid some money to go buy them a snack from the store across the street while they sat and chatted in the teachers’ room. And I know enough Nepali now to hear when a teacher is ordering students around with the tã form—the lowest-intimacy of the four Nepali second-person pronouns. While tã is not necessarily culturally inappropriate for a teacher to use with a student, it’s generally considered a rude pronoun in most contexts outside of direct family, and is certainly not a polite or respectful way to speak to anyone. Some differences are cultural, of course, but not all of them. It’s difficult for me to see my students, whom I love and have grown close to, treated so often by the teachers as if they are not important.

Perhaps, more than any amount of English, that is something that I can teach my students during my time here. As the end of my journey draws near, I have naturally begun reflecting a bit more on whether I accomplished my purpose (well, my stated purpose, anyway) of improving the English level at my school. And to be honest, maybe I am still among the trees, but from where I stand it doesn’t look like the forest has gotten too much better at speaking English.

And yes, my official title is “English Teaching Assistant,” but I still have the narrative power here, so I might venture to put forward a different perspective that will make me feel a bit better about myself (and it might even be true—or so the writer would have you believe): that teaching English, per se, was not actually the most important thing that I could have done for my students. Rather, in a system which ignores individuality, a system which often sees these kids as worthless, I have entered the classroom every day with kindness and put the students first, I have done my best to show them that they matter. And maybe that’s the best thing that I could give them after all. Though we’ll see how much it helps them on their exams next week.

This essay was original published by Oren Karp on his Nepali Dispatch blog and is posted here with permission from Oren Karp.

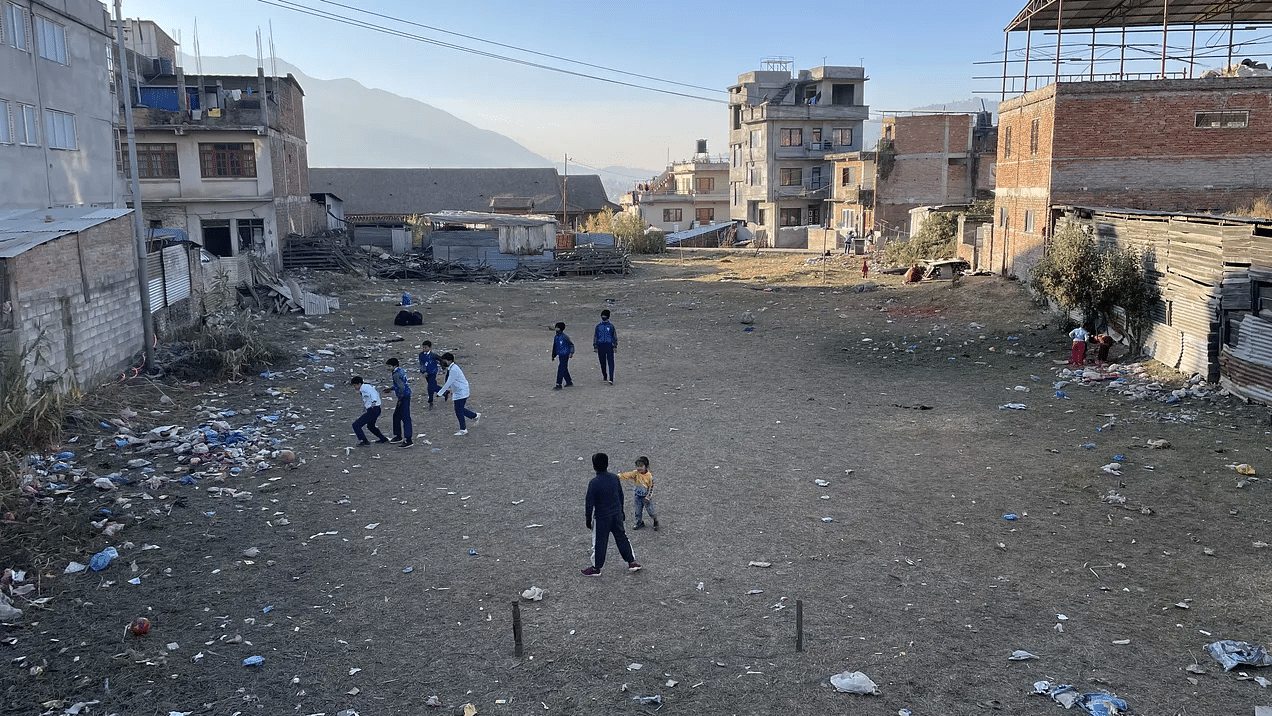

The picture of boys playing soccer after school was provided by Oren Karp.