Or, Gaining a Little Height on Life

[Editor’s note: Oren Karp is a recent graduate of Brown University and a Fulbright Scholar teaching English in Kathmandu, Nepal. He posts an account of his life in Nepal every few weeks.]

It’s hard for me not to see the last nine days as a little taste of what might have been. I’m not usually one to dwell too much on the past, the what ifs, but I don’t normally get such a clear glimpse of my potential reality so sharply juxtaposed with my actual one. Living through the past two years has meant, for all of us, living in a different world, and while I had trouble accepting that world at first, I have gotten used to living here without worrying too much about other possible existences. So when that particular regretful feeling twisted in my stomach, it was melancholic and familiar.

The beginning of the month passed as normal, bringing with it the much-anticipated end of our language classes and orientation. Almost everything about my life here so far has revolved around the office where I was going four or five days each week to meet with my cohort, take Nepali lessons, and sit through presentations. But after nearly two months, our routine has come to an end. Two Fridays ago, I went to my last language class with the whole group, my last lunch at the restaurant right around the corner (I had just started to mix it up, ordering momos and chowmein rather than daal bhaat every day). It has been a long time since we arrived, and I think we are all ready to start doing what we came here to do. But I am a creature of habit, and it’s always sad for me to let go of knowing that I will have a reason to see my friends every day. Yet that’s what life is: new routines replacing old ones.

And with that last day at the office complete, we found ourselves at the beginning of a 10-day vacation, the country suddenly and vastly open. Five of us, including me, had planned beforehand to go on a trek together and jumped through all of the hoops necessary to make our trip happen. This involved not only booking a transportation and preparing all of our gear, but also tasks such as submitting travel requests to be approved by the US embassy and getting Nepali permits to travel (bureaucracy knows no borders). I felt that specific excitement and anxiety of an upcoming trip: looking at maps and trying to fit everything I needed into my bag, Googling packing lists, double- and triple-checking that I had my passport and other documents.

Then, suddenly, on Saturday morning, we were off. The five of us climbed into a jeep and slowly Kathmandu faded behind us, the clouds of dust becoming clearer as we carved through mountains and valleys. Roads have no sense of consistency here, except that all of them are inconsistent. No section of road is completely unpaved and rocky, but no section of road is completely paved either; driving well in Nepal means skillfully navigating the bumps and ruts to get the car onto the next smooth section with the least trouble. We soon found ourselves on the edges of mountains, bouncing over obstacles while enjoying beautiful views of terrifying drops just outside the window. The drive—about six or seven hours—left us relatively unscathed, except for maybe bumping our heads on the ceiling once or twice catching air over potholes.

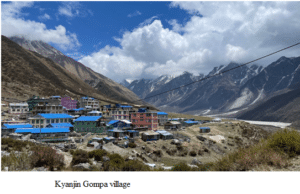

Langtang National Park isn’t the most popular tourist destination in Nepal, which is part of why we chose it. But the biggest reasons were its proximity to Kathmandu (it’s closer than any other major trekking route) and the fact that none of us had been, since some of the group had spent time in Nepal before and done some other treks. The basic itinerary for the Langtang Valley trek is three days of hiking up the valley, a day hike at the top, and then three days back down. We followed a muddy-green river the whole way, beginning in hot, wet jungle and breaking out into exposed, rocky land where the wind whipped our sunburnt faces as we looked up at the mountains.

Trekking here has a different pace to it than any other outdoor adventures I’ve done before. As you walk the trail, you follow winds through villages the entire way up, usually filled with places to stay and people offering a place to sit and have a cup of tea in the middle of the day, a room for the night at the end of the day. These tea houses, as they are called, serve as good markers of distance, how far you have gone and how much remains for the day, but they are also basically hotels, which means you need to bring much less food and gear with you than you otherwise would. Every day of the trek, we stopped at a restaurant for a hot lunch, usually overlooking the river or distant ridges. And every hotel has an attached restaurant, usually including a big common area with a wood-burning stove and couches where you can sit while your food is prepared. They offer boiled or bottled water, and the rooms have beds and blankets, though sometimes a little extra insulation is nice higher up. The result was that my bag really only carried extra clothes and a few personal items, the rest being supplied by the places we stopped at along the way.

And the mountains, of course, the mountains. They blended into each other, massive, beautiful, only getting higher the further we hiked, as if they were trying to outdo us with every step. At the beginning they were tall, with gaping cliff faces exposed over the river between the lush trees that covered them from top to bottom. But by the end they were taller than tall, so big that hiking from the last village to the highest visible summit would be the same as hiking from sea level to that same village. The mountains here are new, and you can feel their rawness, the sharp points and exposed features that have yet to be worn down by water and weather. You can understand where so much of Tibetan Buddhist imagery comes from when you look at them and see the clouds licking their peaks, swirling down their ridges and valleys. Looking is all you can do, narrowing your eyes into the bright reflection of the sun on snow gently capping their crests.

People have been trying for a long time to put words to the feeling of being among the mountains here, so I will not try to outdo them. There is a certain scale to the Himalayas that just leaves you behind. It is a feeling of surrender, a peace that can come only from touching a force impossibly huge, so huge that you disappear. How can you think of yourself, whatever pain the ups and downs are bringing, when you are surrounded by these giants? The effort of hiking, the outside problems you bring with you to the peak, they are all released by the sweetness of the earth, running down clear like a river from a glacier.

For me, the best part about the tea house system, aside from lighter packs, was being able to meet so many other people as we hiked. Other travelers for sure, many Europeans, some Americans and Israelis and other South Asian hikers, traveling on their own or with friends or with groups of people they never met before arriving in the country. And we met other Nepalis going trekking as well; it’s not an activity relegated to international tourists alone. Yet Nepal’s tourism industry is slowly recovering thanks to the mountains’ call, which brings people here from all over the world here to gape in wonder like I did. And the tea houses brought us together, in many unlikely groups, so that we could get to know each other along the trek.

Besides the other visitors, the journey provided the opportunity to meet many locals along the way. Speaking decent Nepali myself at this point, I felt like I was able to talk with the people I met in ways beyond just asking for a room and ordering food. On the first day, sitting in a hot spring by the river with an older man who put his pants on when he saw us coming to join, I spoke and listened to him tell me about how he used to have to walk five days to Kathmandu. In tea houses, we started up simple conversations with the families working there, often kids who looked like they might be in high school or college. The porters and guides were always surprised and happy that we could speak some Nepali, and we would often ask them about the route and about themselves. Passing through towns while hiking felt different from hiking I have done in the US. The land we were moving through was home to others, but rather than being completely separate from those people, we were traveling with their help, interacting with them, supporting them in return. It was cushier than camping, sure, but it felt more fulfilling, too.

And now I’m back in Kathmandu, the clean air and water and the people, like their land, left behind. Tomorrow I begin teaching, the job that I originally came here to do, though it has been so long that I nearly forgot. And I can’t help but think about where I might have been: When I first applied to be here, I thought I would be placed much more rurally, in a village maybe not too different from the ones I was seeing on my trip. And in some ways, that is still the kind of experience that I want. There is so much that might be different right now, and though I cannot say if it would be better or worse, I cannot stop myself from wondering about it. I think it is at these moments, right on the cusp of a big change, when I find myself unable to avoid confronting these other worlds in my head. But here I am.

There is joy here too, to be sure, and many things to be grateful for. In the week before my trip, I joined all the other school teachers for home visits, which involved walking through a light rain to different students’ houses where we stepped inside for a minute to talk about results and enrollment, turning down cups of tea. Most houses don’t have an address here, so we spent much of the day just wandering through the outskirts of town. When we successfully found a house we would ask the kids there to guide us to nearby houses, a strategy that met with middling success. But being in students’ homes was warm and intimate, especially considering I don’t even really know them yet. It made me feel closer to the kids and the teachers, and it held the weight of the year which is to come. That experience, though I didn’t know it at the time, is the one I am now holding on the scale against my trip into the mountains. And there is my host family, and my friends, the home I am making in Kirtipur.

So I am once again on the edge of something new. In fact, I wrote much of this originally on Monday, thinking today would be my first day of school, but it turned out that I didn’t have school today, and tomorrow really is my first day. Sometimes things work out like that: I would’ve planned differently, written differently, had I known what today held. But instead I walked to my school in the morning, sat in the dust and waited to see if anyone else would come, thought and rethought all the decisions I made in the past 24 hours. And now I am home again, soaking my laundry, trying to keep cool, wondering what the future will bring.

The height I gained walking up into the clouds, I think, is sticking with me. There are always things that could have been, I suppose, from last night to the ten months I’m spending here and beyond. Normally, as I said, I avoid thinking about this kind of thing, but today I’m not afraid to sit with possibilities. Maybe there is value, heading into the familiar unknown of tomorrow, in understanding my life backwards, not peering up from the plateau of the real into the imaginary, but standing among the clouds of the imaginary and gazing down onto the expanse of what is. I usually prefer to pass my life on terra firma, avoiding my fear of being high up, contemplating the drop. But, in this case, it was leaving the ground that helped to show me the things I’m missing, and conversely, to illuminate the things I have. It just took a little height to see what I really have here in Kathmandu.

This essay was original published by Oren Karp on his Nepali Dispatch blog and is posted here with permission from Oren Karp.

Pictures were provided by Oren Karp.